Kate Orme is a multidisciplinary practitioner with an emphasis on making sculptural work, which for Orme, is “the most anthropomorphic discipline of the arts”. This a hugely important sentiment as it provides the artist with a gateway for exploration into the deeply rooted questions of existence, spirituality and the afterlife. Many of her works have a naturalistic sense which connect viewer to thoughts of the environment, our place as humans within it and the fragile nebulosity of the two’s relationship.

In a piece entitled Winds at the Edge of the Universe (Picture below) Orme questions the very nature of the universe with an elegantly minimalist interpretation. Both the title and transparency of the Perspex are suggestive of existential solitude yet the purity in colour and form locates the emotional responses in a place of serenity. It’s a remarkable use of word, form and colour and is testament to Orme’s material and conceptual proficiency.

Orme adds another dimension to what is already a deftly layered output by infusing materials with private meanings. Each material alludes to a personal aspect of her life, whether it’s a personal history or closely held belief. Encoded in her work is a discreet lexicon, the meaning of which is purposefully suppressed, permitting viewers to delve deep in to a narrative of wistful speculative musings.

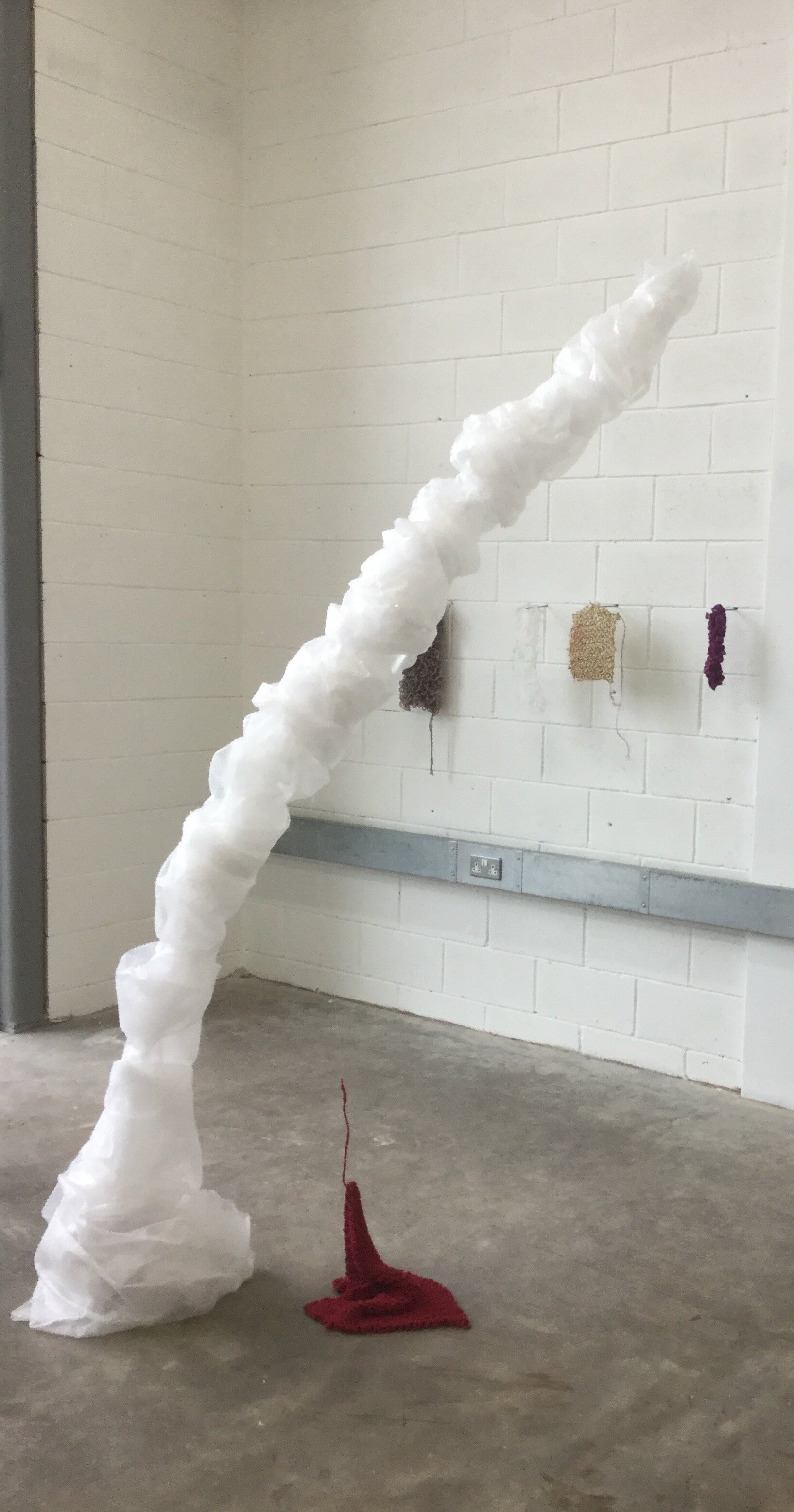

‘Elemental Me’ was Orme’s first solo exhibition which ran from 8th-25th May 2019 at The Yorkshire Art Space, Sheffield. Its sees the artist developing her sculptural practice into the realm of installation as the space is transformed in to a unified art-scape. Twisted fabric forms rise form the ground looming high in defiant of material expectation, an organically knotted totem grows upwards and extends its tendrils searchingly across the floor, there are signs of wounds and healing as limbs are wrapped in bandages. The show itself is instilled with a sense of life, populated by forms that appear to be growing in a quest to discover the shape of their very own bodies. ‘Elemental Me’ is a place open to exploration, a physical narrative to be read and interpreted by is passing guests.

Afterview’s conversations with Orme is a step towards decoding her fascinating body of work and the processes that give rise to such intriguing forms.

Interview: Kate Orme

Q1) Please could you start by giving us and the readers a little background information. We are especially keen to hear about how your past experiences have informed your work as an artist.

I was a nurse for a long time before I started making art. It teaches what is important in life, to cut to the chase and not waste time on extraneous stuff, and whilst that can blinker you to the bigger picture it also gives you great focus and allows you to ask the big questions. My work is mostly three dimensional so I'm interested in the fabric of space right down to the level of subatomic particles, and how we occupy that space. I worked with human bodies, I like people, with all our foibles and concerns with life, love, sorrow, grief, death, kindness, joy and happiness. I wonder about consciousness, is it real? Are we real or just an illusion? What is life? What is death? Is there life after death? What is time? What is space? What is the universe made of? I think that because I have literally been elbow deep in 'life ' the question of an afterlife piques my curiosity a lot. No wonder there is no room in my head for extraneous stuff. And yet ......the devil is in the detail. I began making art after my children had all left home and I had given up my career as a nurse. I decided that at fifty one years old it was time for a change. I had been quite happily defined by my relationships to others and my career but it was time to step away from those definitions and discover who I was as an individual. I began by exploring my roots, then to use that as a firm rock to stand on. I completed a pre -BA Foundation at Dewsbury College, then a BA Hons in Fine Art at University of Leeds and finally an MA Contemporary Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam. I now work from my studio in the Yorkshire Artspace in Sheffield, which I love.

Q2) You are currently based in Sheffield which has experienced somewhat of a renaissance in recent years. Could you tell us about the role it has played in your practice and the importance this renaissance it has had in the community of Sheffield?

None of my friends and only one of my extended family are artists, and I live in a rural village away from any arts organisations, (although I now have two near neighbours who are artists), so when I graduated from Sheffield Hallam after my MA I needed to stay with some sort of arts community both for support and to help me grow. After a year on the waiting list I got a studio in the Yorkshire Artspace and have been there since. On a daily basis we don't spend time in and out of each other's studios, we go there to work, but we do have a fantastic support network with opportunities of workshops, seminars and an exhibition programme to help smooth our professional paths. My studio is my safe place where I go to think and work in private if I want to without interruption. We have a yearly open studios event which has been very important for me in terms of developing work, getting feedback and growing confidence, so that I now know that I am ready for my first solo exhibition. The arts have been very strong in Sheffield for some time and now all the galleries, studios, arts organisations and the council are talking together even more. A plan for the future has been commissioned so that now Sheffield arts will be even more cohesive. Sheffield is buzzing already, I am really looking forward to see what the next ten years brings.

Q3 We are interested to hear about your experience at The Trelex Residency. How did you find the challenge of working with the immediate environment, and what did the landscape of Switzerland bring to your work?

The Trelex residency is an extraordinary concept and place to work. The director, Nina Rodin, offers artists a place to think, develop and work with no expectation of what might come of it. There are no application forms or hoops to jump through just, as you might imagine, a long waiting list. Nina trusts that artists know themselves when they need a safe place to ponder, examine, play, talk and exchange ideas with other artists and she says that to date no one has abused that trust. Trelex has been a very important experience for me, both I terms of practice development and forging long lasting meaningful connections. Trelex now has many alumni, it is an extended family with members from all over the world and it offers great support and cultural exchange. Nina has a degree in astrophysics, a doctorate in neuroscience and an MA from the Slade so I couldn't have wished for a better sounding board and now a treasured friend.

During my BA I was based for three years at Longside within the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and fully immersed in that landscape. I live in a rural location so living in the Swiss countryside in the space between Lake Geneva and the Jura Mountains wasn't so out of the ordinary for me , except of course for the mountains. I think of the environment, whatever it may be, as just another material to be considered in the whole picture. During one visit to Trelex I was sure before I went that I wanted to work high up in the snow. When the earth is blanketed in snow and it is completely white, and when sound is muted or nonexistent because it is absorbed by the snow there are no distractions, only the work is apparent. There is a sort of clarity that comes with that. I make the distinction between making work within an environment which has no relationship to the work other than being a convenient place to work, and working with the environment as contributory factor even if only as a juxtaposition. I had intended to use the snow and isolation as an environmental location which would make other dimensions more visible but not everything works out as you wish. Working in the mountains throws up problems like the weather not being what you ordered, so you adapt. Your thinking has to swerve and you end up with something unexpected and exciting to ponder, all good stuff. The snow was thigh deep and too soft to work in, I made a good start but that work is still unresolved. It doesn't matter, I'm in no rush and I shall get back to it when the right opportunity presents. The other huge things to consider when working outside are scale and integration, or not. Sir Anthony Caro once told me to remember that when placing something outside you are putting it on the surface of a planet. Those words have stuck with me, as they would! and although they are massive considerations nature always has the last word.

Q4 Your work ‘Songline’ draws on beliefs form the Aboriginal culture of Australia and is demonstrative of an important exchange of cultural ideas which all artists rely on. There seems to be a process reinterpretation in your work, even with works that draw on scientific concepts, you appear mold and manipulate ideas to your own expressive will. Could you provide us with an insight into this aspect of your work?

I think that I am a sort of magpie. Bits of things, ideas, snatches of conversation, throw away remarks, a new material catch in my consciousness and I collect them for future use if they are appropriate. It was serendipity that someone I had never met or seen before walked into my house one day and said ' I understand that you have lots of books, I've brought you this one to read and I'll take one of yours' , I was so surprised that I agreed. The book given to me was 'Songlines' by Bruce Chatwin. I was exploring what my roots meant to me at the time and how I felt about the fact that as I only have male children they cannot pass my mitochondrial DNA to their children. The buck stopped with me. After reading Songlines I got some comfort from the cultural idea of singing up your ancestors. Although we apparently and notoriously misunderstand information given to us by this culture, who also apparently and notoriously tell us what they think we want to hear, so none of it may be true but I loved the idea of singing up my granny and my great granny etc. even if only for a short while. I didn’t give back directly to the Australian Aboriginal community but I hope that any conversations started by viewers of Songlines might count as my contribution towards cultural exchange. I've done the same sort of thing with the scientific concept work, a chance remark may spark a question. I am an atheist. In my previous career as a nurse I have watched life leave a person, washed and cared for their mortal remains and been quite convinced that when you're dead you're dead. There's nothing else, not a spark, nothing. It's been a pragmatic viewpoint and has directed my curiosity towards the solidity of scientific explanations. This has been reinforced by my sculptural practice. It requires me to be aware of space, what constitutes it, how it is measured, how it travels, how it is altered, how it relates to my work and how my work relates to it. However as much as I am curious about space I am not a scientist. I research as much as I can understand, even visiting CERN, but I have more questions than knowledge. I am a visual communicator so in an attempt to formulate questions in a simple way that I can understand I use my visual language skills. In 'Winds at the edge of the Universe ' I had been told that scientists are working in twenty two dimensions, I am only conversant with four, and they have postulated that there may even be parallel dimensions. Because I am ignorant of the facts my imagination is able to take ridiculous leaps. 'What if the nothingness between dimension is so thin in places that you could tear a hole in its fabric and peer through into something else?'. And that was the beginning of that work, sort of. I remembered that I had burnt holes in small Perspex squares but couldn't decide why they meant something to me, I remembered the projected shadows as the sun shone on them and that was my light bulb moment, the recognition of what they were, or could be. There were other considerations to take account of, for example where the edges were, and delights when I realised that hole in the Perspex gathered up reflections of exterior life and swirled them into a maelstrom of blurred reality before it swallowed them like a black hole. So the question was there, there material was there, I just had to make decisions about scale and installation. The material spoke for itself, the material is the work. There was no hard construction trying to fit the material to the concept, no false dichotomy between concept and material because the material was the concept. The work sits more easily because of that and doesn't get in the way of the question, it enables the question. It is a quiet piece, most of my work is quiet in this way. It is not always easy to situate quiet work into a noisy bright art world but it is who I am and I have a lot more questions to ask.

Q5 In regards to your solo exhibition ‘Elemental Me’, how did you find the challenge of filling an entire space?

I didn't really find it a challenge, the most difficult decisions had already been made before I came to install. Which pieces to include, did I want them to be a gallery of standalone works separate from each other, or for them to be separated but integrated parts of a whole with connections to each other. I chose the latter because although they were all quite separate elements with their own unique characteristics and meanings, they were a part of a 'whole me', so I wanted them to have a relationship to each other. The way I managed that was directly related to the gallery space. I don't see an empty space as empty. For me it is full almost solid with its own weight and density. Before I started to install I spent a day in the 'empty' gallery, feeling the weight of and within its dimensions, seeking the edges, the corners and any small anomalies that might interrupt the flow. Each time I placed an element the dynamics of the whole space changed but if you get the first element right then everything flow from there. That's why it was so important for me to know the possibilities and constraints before I started. It's a valuable time spent as what you think you want to do doesn't always match what is possible in a space. During installation there is a point when you think it's not enough, you haven't done enough, but that is just panic. You have to trust the judgements you made before you were in panic mode and stick to them. The space wasn't a white cube, there were different ceiling heights, square corners, a curved convex wall and a distinct path around the perimeter so I had to be flexible and work with the space. I was happy with the end result. The work had plenty of space to breathe in, the separate elements were quite distinct from each other, but it felt like a cohesive immersive space with a purpose.

Q6 Your work ‘If Only’ uses materials in a way to suggest a poetic yearning - as a smaller form reaches up in desire for a much larger form towering beyond its grasp. This work demonstrates an anthropomorphizing of the inanimate, common in much of your work. Are you able to shed some light on your process when working with materials, what comes first in works like these, do you start with the emotion and construct the materials to express it. Or do you find the emotions within materials?

I think in general that sculpture is the most anthropomorphic discipline of the arts, purely because it sits/stands/ lies (all human attitudes), within the same dimensional space that we humans inhabit. In 'Elemental Me' that is emphasised because each 'element' is a reflection of a part of me, a human being. I think that having been a nurse the life form I am most connected to is the human one. I've probed it, washed it, soothed it, healed its hurts, and felt its pain, felt its joy, sadness and heartbreak. Human life and death is in my bones but it also sits very close to the surface of my skin, so that probably goes some way to explain that thread that weaves its way through my work.

As for what comes first emotion or materials that's difficult because it's not always the same. For 'Elemental Me' the thoughts of who I am and some of the elements of my personality came first. The materials practically chose themselves. Every material I use presents itself complete with its own personality, how strong or weak it is, how heavy or dense it is, it's translucency , it's texture, it's colour, it's permanency and most importantly it's perceived usage or purpose (with all of the connotations they bring), and any histories . They all tell their own story so I try to be sympathetic to that. The worst thing I could do would be to push their individual properties beyond their meaningful capabilities, it simply wouldn't work. In contrast for 'Whispering Sticks', the work subsequent to 'Elemental Me’, the material came first. I was given a tin of buttons with the words 'there are three generations of my family's buttons in that tin '. Sharp intake of breath and thoughts of what am I going to do with theses then? There were in fact more than three generations worth and I felt a huge responsibility to do justice to their histories. I would wake up in the morning and think 'oh yes I know exactly what I'm going to do with them' but by evening that idea seemed awful. It took me some time to figure it out but the main thing was that I needed to be sympathetic to the buttons. The final work was well received, many people left in tears and one young woman asked if I would give her a hug so I think I managed to give them a voice. There can be a problem with letting the materials tell a story with no references other than the material, and that is that the end result might be a bit ambiguous, which is another reason why choice of material is so important. It's a very fine balance, to give some freedom whilst all the time you are gently directing. A bit like parenting really.

Q7 Lastly, we would like to offer you the opportunity to inform our readers of what lies ahead for you as an artist.

I have a few more exhibitions lined up for the next couple of years but I'm not counting my chickens just yet, sometimes things just don't happen but I have my fingers crossed. I want to continue to develop new work, although the same thread of life and death still runs through it. A chance tale of twins crossed my ears this year which got me thinking about the random nature of fate (if there is such a thing), and altered states of consciousness, and I'm developing those alongside a growing interest in palimpsests . So I'm very excited about the next couple of years,watch this space !

Readers can keep upto date with Kate Orme’s work at the following sites:

https://www.instagram.com/kateorme2018/

https://twitter.com/KateOrmeArtist

Author: Afterview

Photographs courtesy of: Kate Orme and The Yorkshire Art Space